Original Version

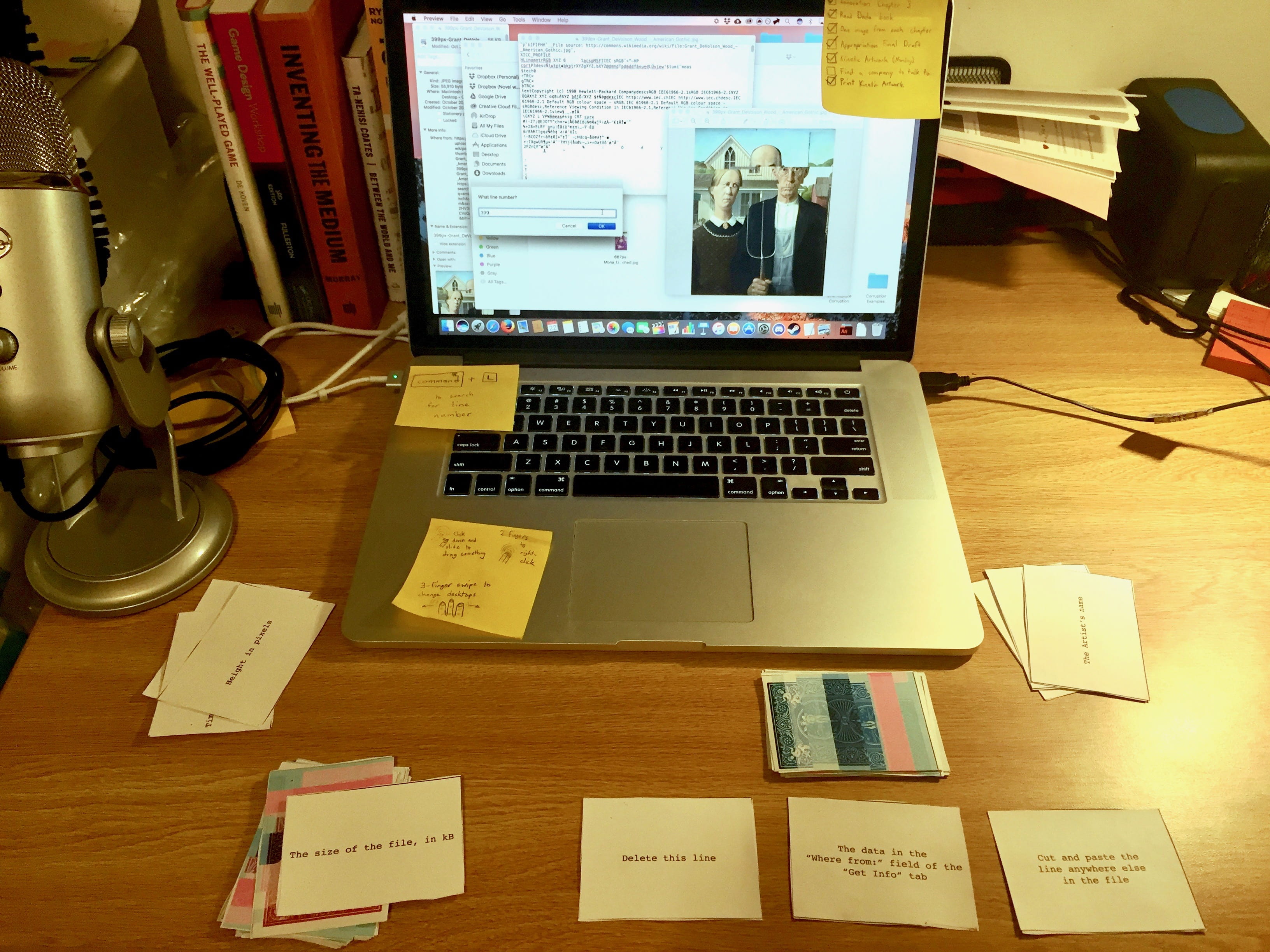

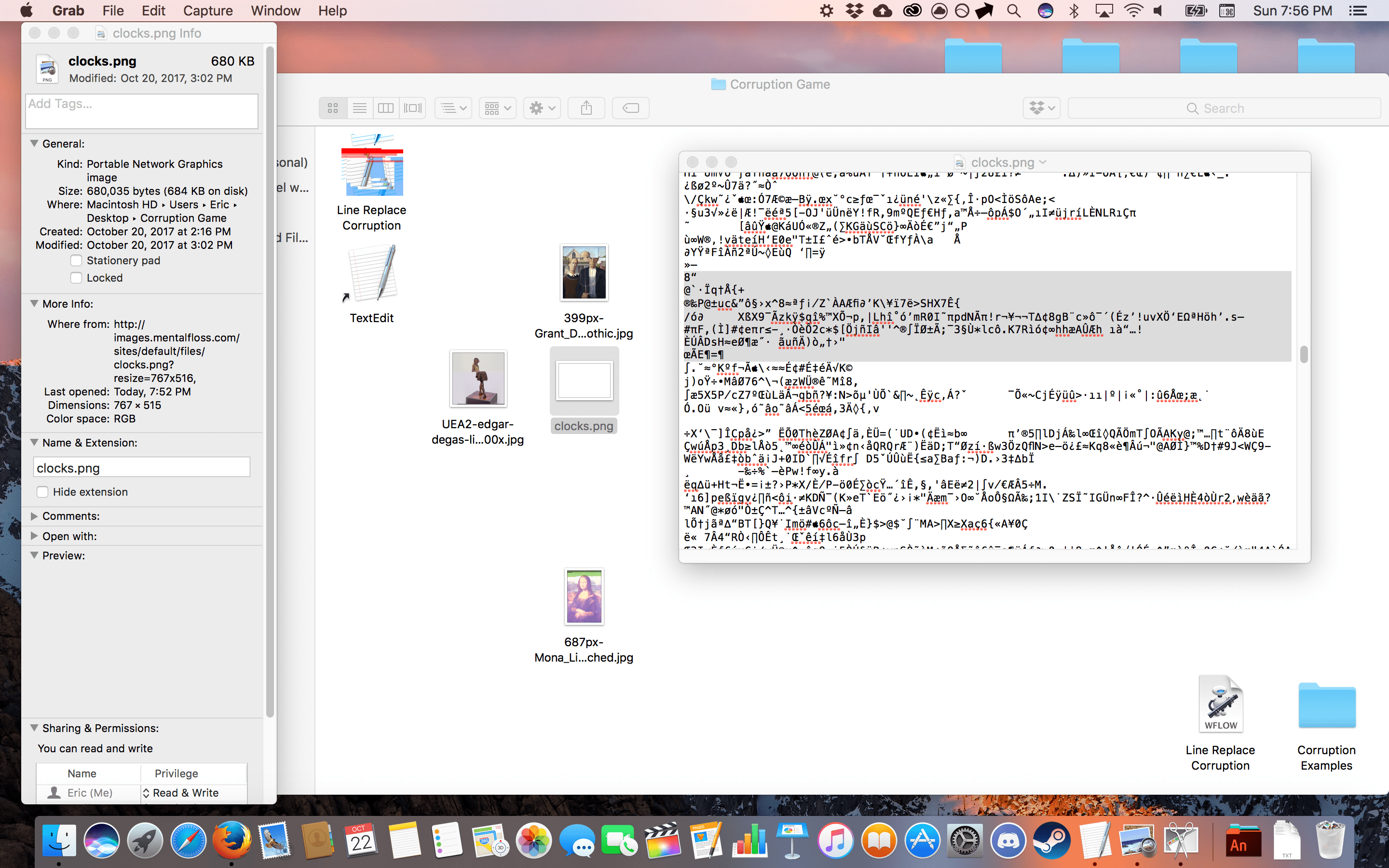

In the original version of Shot-Pong-Chip, players take turns placing chips in the shot glasses. When they make a row of 3 continuous chips, they get one point. When they make a row of 4, they get two points. Each point gave the player access to one pong ball which they could use to block off shot glasses without having to “take a drink” (metaphorically, not literally). When the player “takes eight drinks,” they “black out” and must stop playing. The player with the most points wins.

New Version

The new version increased the power of the pong balls to inspire players to remember they do not have to drink every turn and to add more tactical choices to the game. Each player starts with 3 pong balls, and gains one extra one if they gain a point. This ball, if chosen to be used, is taken from a cup in front of the player, which gives them access to the ball but also opens up another shot glass to use on the board. As it plays similarly to a large tic-tac-toe, more chances to actually lock off board spaces allows interesting strategies.

Meaning

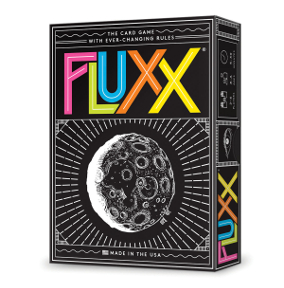

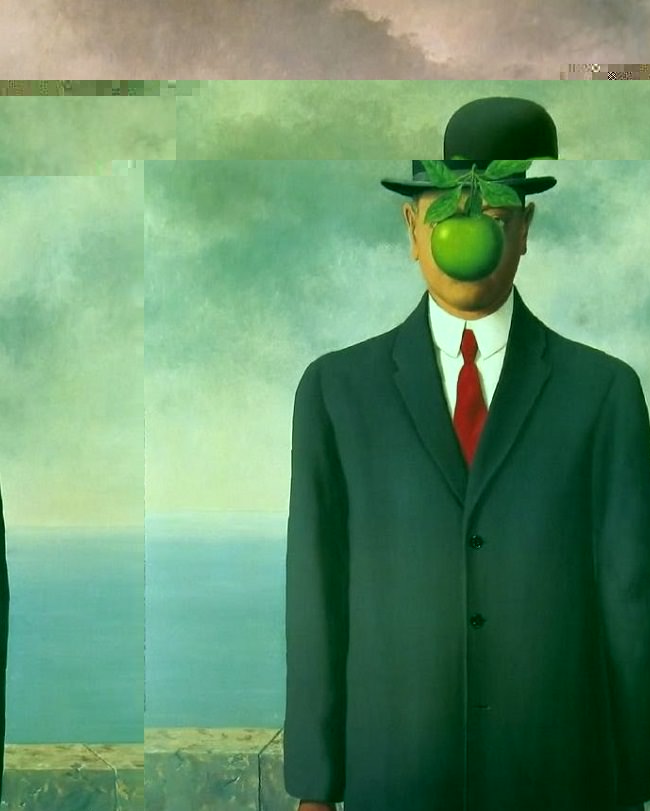

I wanted to create something that purposely played with known game mechanics and some game pieces. Similar to Yoko Ono’s piece White Chess, I wanted to have people feel familiar enough with the mechanics, and in some cases the pieces, but used in a different context than they were used to. The game is designed in a way that creates stalemates and/or so that players that choose not to drink much usually lose. This fits into the theme of the game which comments on America’s binge-drinking culture and how nobody truly “wins” in this culture. Because of this, the items of disposable shot glasses, beer pong balls, and poker chips are used in order to drive home the point of collegiate drinking patterns which usually leave people sick, miserable, or in dangerous situations. I purposely chose objects that are used commonly in “drinking games” in order to make a game about drinking, but not one in which the player is recommended to drink. I was somewhat inspired by the idea of “readymades” by using easily obtainable items that were already in form to be used, all they needed was to be put together in the correct context for this game. This also draws from different appropriative Flux-kits which commonly used approrpiated objects in order to present a sometimes game-like artpiece all in one box.