The Game:

Super Mario Bros.: Just-Like-You-Remember-It Edition! features five levels of memory-deteriorating fun!

Built upon “Super Mario Bros” by Github user Gold872

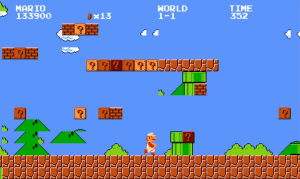

…which is recreating some old video game from the 80s or something.

Artist’s Statement:

If you’ve ever played the game Super Mario Maker, or its inventively titled sequel Super Mario Maker 2, you’ve perhaps encountered the many remakes of Super Mario Bros.’s first level, 1-1. These are plentiful and unavoidable when playing this game online. Some people twist the level, adding traps and fire bars everywhere. Some remakes are perfectly accurate, but most aren’t. Many of these remakes get small details in spacing wrong. Some of them miss entire parts of the level. As time passes, which details of the games we play are we still able to remember?

I’m not sure I remember it like this… (pictured: Super Mario Maker 2)

This game project was primarily inspired by the plunderphonic works of Daniel Lopatin (AKA Oneohtrix Point Never, AKA Chuck Person), James Leyland Kirby (AKA The Caretaker), William Basinski, and various artists in the vaporwave genre, as well as the appropriation works of the Dada movement.

Daniel Lopatin in 2010, under the pseudonym Chuck Person, released a limited-run cassette tape of 80s pop songs looped, slowed down, and distorted into what he coined “eccojams”. By taking somber lyrics of songs out of context, Lopatin creates a haunting reinterpretation of these once-hits. These eccojams are heavily concerned with the idea of memory. They feel like distant memories of one part of a song, randomly getting stuck in one’s head years later. Lopatin re-released several of them on his audiovisual project “Memory Vague”. He approaches the idea of memory deteriorating at the end of the tape’s first side, where it gets more and more distorted and noisy until the original sample has been fully drowned out by a pulsing harsh noise.

Another artist even more concerned with the deterioration of memory, specifically in relation to neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s, is Leyland Kirby, who produces music as The Caretaker. The Caretaker’s most well known albums, “An empty bliss beyond this world” and “Everywhere at the End of Time”, are based on a study where people with Alzheimer’s were able to recall associated memories from the music of their youth. Both albums feature 1920’s music scavenged from record stores, looped and echoed into distant memories. “Everywhere at the End of Time,” Kirby’s final project as The Caretaker, is comprised of six stages reflecting the progression of Alzheimer’s disease. Kirby’s work is often compared to William Basinski’s “Disintegration Loops”, an album of tape loop experiments where the tapes continually deteriorate as they’re played.

The Dada movement saw many artists (although they themselves at the time may have rejected the term, time and Wikipedia have come to know Dada as an art movement) appropriating found objects, twisting their meaning and purpose into new subversive works. While these artists were very interested in specifically using found objects, I am mostly interested in the way these repurposed objects lose or alter their meaning. When Kurt Schwitters repurposes machine parts, old newsprint, or bus tickets, they lose their ability to function as intended. Using these appropriated works in collage puts them in a new context and assigns them new meaning. When Marcel Duchamp creates a readymade statue out of a bicycle wheel or a urinal, he assigns it new meaning as a work of art. I love this idea of assigning new meaning to existing things through selection and transformation.

These projects got me thinking about applying the idea of memory deterioration to games. Artists like Basinski use the decay of physical artifacts to create their art, but digital games don’t degrade in the same way. I wanted to capture the idea of a poorly-remembered level, such as that seen in Mario Maker 1-1 remakes. I wanted to loop one piece of a game into infinity, like Daniel Lopatin or Leyland Kirby did with their music. I wanted the entire thing to collapse in on itself by the end like the Disintegration Loops, because at some point, everyone’s memory runs out.

I originally wanted to use a game other than Super Mario Bros., but it was the easiest to find an accurate recreation of to modify for this project. It also worked well to work off of a game with wide familiarity, since the game should ideally be concerned with a level the player actually does remember. I took the structure of 1-1 and created five levels from it.

The first level is exactly 1-1, recreated perfectly, in a fairly accurate recreation of the original game.

The second level is slightly off. The spaces between key moments of the level have been altered, and powerups may be in different locations. The music has been slowed down slightly. This level is meant to represent misremembering the small details of the level design, as many Mario Maker recreations do.

The third level begins repeating key structures of the level, or forgetting some entirely. The music does something similar, repeating portions of the iconic overworld theme and skipping occasionally.

The fourth level repeats the beginning of the level over and over again. I consider this the “eccojam level”, as one moment is repeated again and again. The music is inspired by the second eccojam on the tape, called “angel”. It loops one section of the song, speeding it up and down in a disorienting manner. One moment it resembles the original bouncy track, and the next it briefly slows to a chiptune dirge.

The fifth and final level represents the final deterioration of a memory of this level. The level design and background elements repeat and glitch in nonsensical ways, only vaguely resembling the looping beginning of the level. The music is slow and drawn out, randomly pausing for large amounts of time and twisting into sounds the NES would not be able to replicate. Eventually, the iconic features of the level vanish, and the empty land soon gives way to an uncrossable abyss, as the memory eventually fades away.

At some point, everyone’s memory runs out.