The Game: https://alliumonion.itch.io/conversion-protocol

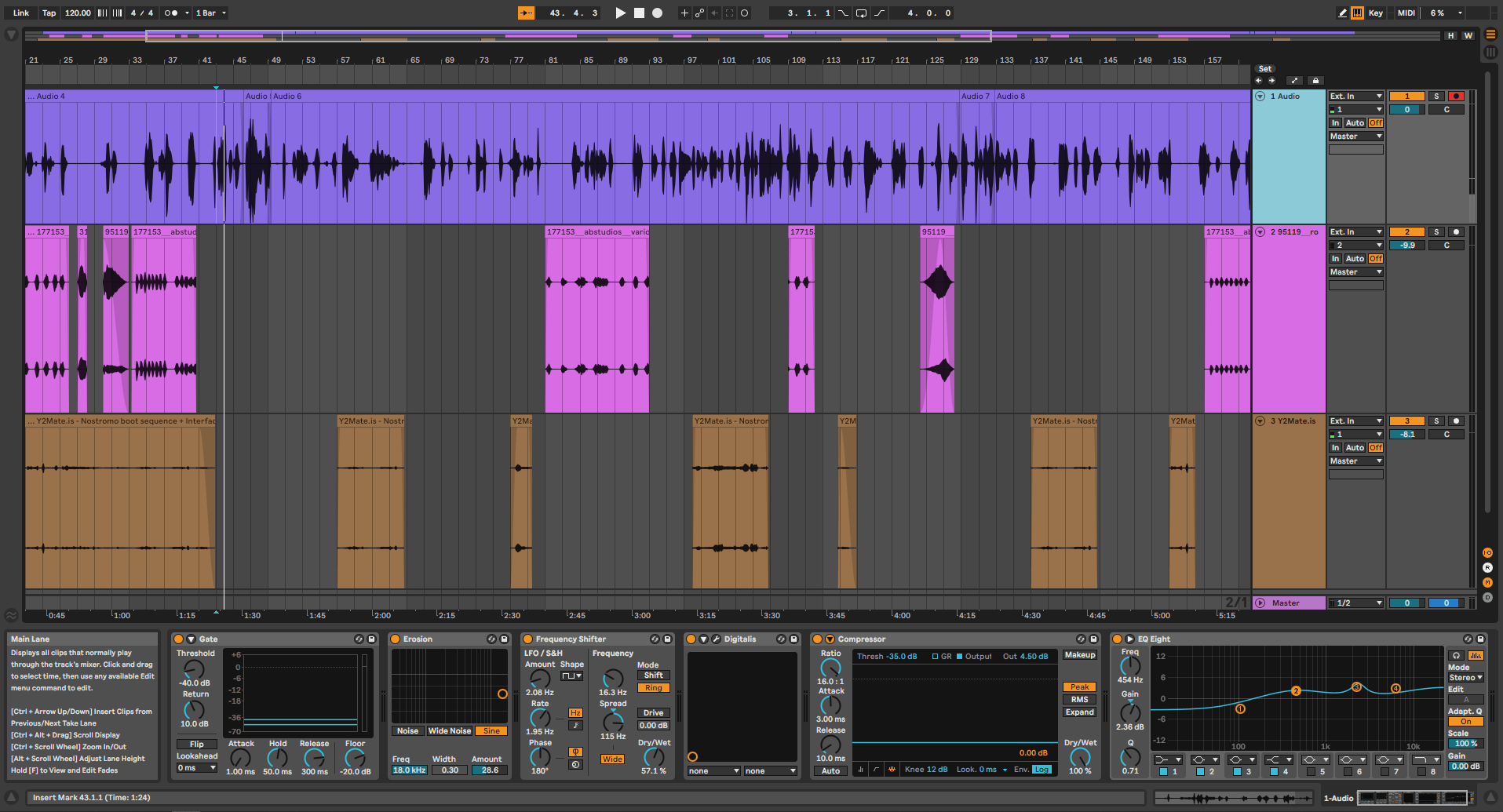

I came into the creation of this game with a simple premise: to create a game in which the player is given an entirely auditory experience. Nothing in the way of any visuals. Absolutely zilch when it game to information transmitted by sight. In a medium so heavily dependent on visual communication, just as humans are beholden to both the powers and limitations of their sight in reality, this results in a significant shift in the way in which the player approaches the game. Having to rely so entirely on the ear to receive information from the game encourages the player to focus their attention on the only information given to them—the sound.

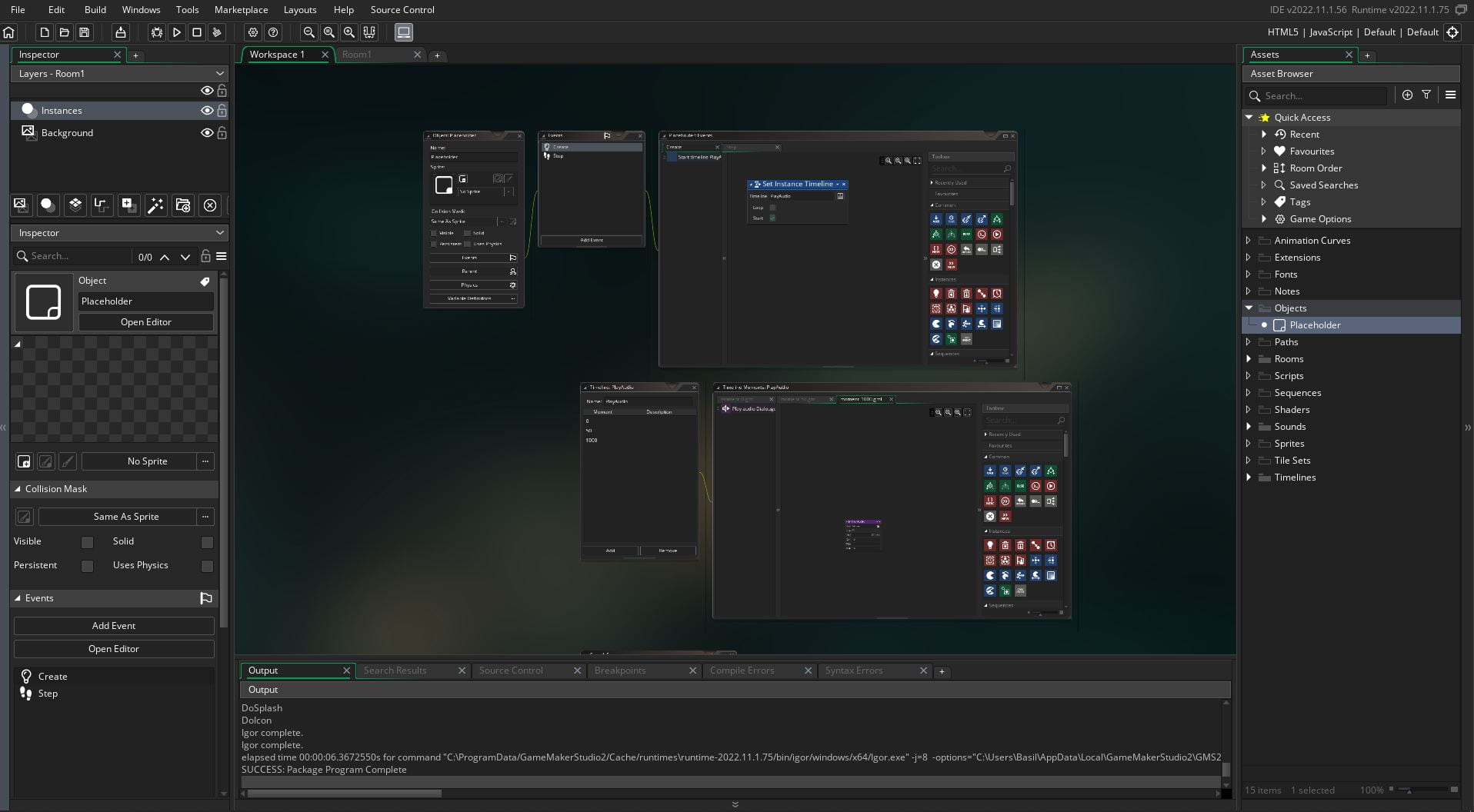

In making this game I encountered a multitude of setbacks which required me to reduce my scope; thankfully, I was prudent when I set out on this project and developed my game in such a manner that I was able to easily reduce scope without damaging the overall experience. My approach for the game’s content utilized my sound design skills, including the array of effects on the voice heard throughout the game. I would have liked to expand much more on the initial premise of this game, but was significantly hampered by life events occurring at the tail end of the semester; however, I am still proud to have managed to encapsulate, what I believe, to be the core concept, experimental mechanic, and narrative experience that I set out to explore. In the creation of this project I also had the opportunity to develop my technical skills, as I worked to make the game run in browser using HTML5. The fruits of my labor can be seen on itch.io using the link above. And I am certain I will expand upon this initial demo of a game in the future.

Documentation: